Flying High: A Review of "Kiki's Delivery Service"

Hayao Miyazaki's masterpiece imagines self-fulfillment as the most powerful magic of all

One of the signs of a great movie is when it still manages to change you emotionally, no matter how many times you’ve watched it. I’ve left movies feeling sad, optimistic, even enraged. Since the first time I watched it as a teenager, Kiki’s Delivery Service has always left me feeling something no other movie ever has: Inspired.

Before my most recent viewing last week, for the first time on the big screen, I had been struggling for weeks with writing. Every time I sat down and picked up a pencil or looked at my keyboard, it was as if I had forgotten how to write in the first place. I felt a bit guilty seeing a movie when I felt I should be writing. After I left the theatre, I could feel myself bursting at the seams with a desire to write once again.

Kiki is an eager teen witch-in-training. One full moon night, a clear night sky, the kind perfect for flying on a broomstick, she leaves her parent’s home in search of a non-magically aided town so she can use her magical talents to help others. Taking along only her father’s radio and her talking cat/best friend Jiji, they arrive at the idyllic seaside city of Koriko, where Kiki is determined to build a new life for herself.

After an initially rough start involving a near-miss head on collision with a bus and a run-in with the police, she meets a kindly couple: the motherly Osono, and her quietly affectionate husband, Fukuo, who give her a room to stay in above their bakery. Since flying is her best talent, she decides to open a delivery service.

Director Hayao Miyazaki typically uses the board driven method to figure out his films. He draws on storyboards first, figuring out the plot along the way, then translates to a more traditional script. As a result, Kiki’s Delivery Service unfolds at a more episodic pace – which makes sense considering Miyazaki spent most of his early career working in television – with Kiki going from one delivery to the next, meeting and befriending different townsfolk, and learning to turn her love for flying into a means of making a living.

Miyazaki has said in interviews that part of the inspiration for Kiki came from observing the women who would come to the city by themselves to pursue careers in animation. The act of making animation and art in general, is a common thread through most of Miyazaki’s work.

There are no quests, no magical creatures (besides Jiji), and no villains to vanquish. Kiki’s opposing force is her own self-doubt, and the growing weariness that comes with being independent and starting from scratch in a strange new city.

The opposing force is something much more common: self-doubt. Kiki experiences set backs, botched deliveries, and ungrateful customers. When a young girl rejects a cake she helped make for a delivery, she begins to lose her confidence, and then she loses her ability to fly, and talk to Jiji.

“Flying used to be fun until I started doing it for a living,” Kiki says after losing her ability to fly on her broomstick. Anyone who has ever tried to turn their passion into a profession can identify with that statement.

I’ve felt that way about my own writing many times.

When you’re young, you fall in love with your hobbies, whether that be writing, animation, or any kind of craft, and at first you practice it simply for the pleasure that it brings you. Once it becomes your livelihood, then it becomes work, and you start to lose that feeling.

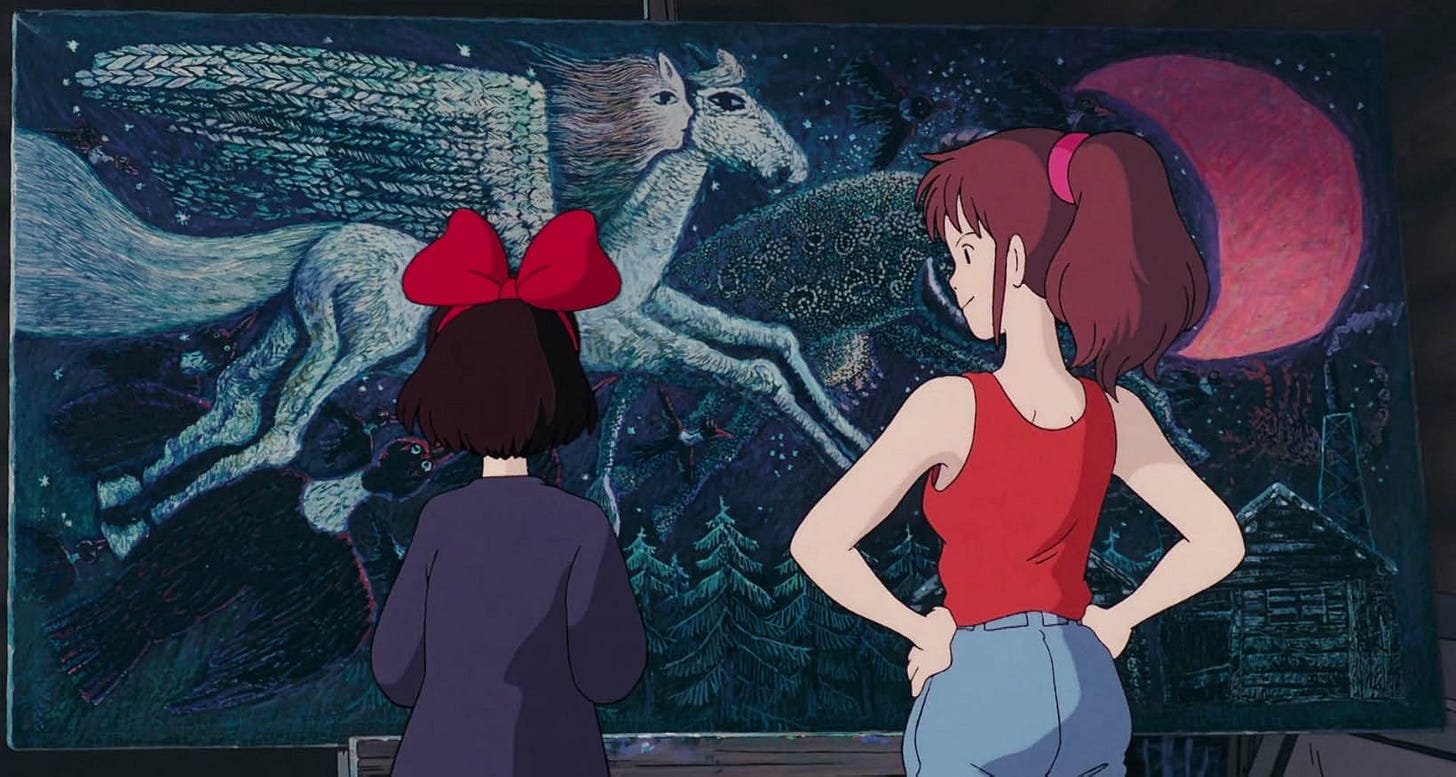

On this re-watch, I sympathized more than ever with Kiki’s internal strife on this watch. When she loses her ability to fly, she feels as if she’s also lost her identity. Ursula, an artist living in the woods, only a little older thank Kiki, who tells her that the key to flying, as it is with painting, or even baking, is to find inspiration. She tells her to take walks, nap at noon, and all the things in recent years we’ve come to call self-care.

I think every person who wants to pursue a craft of any kind should watch this film. Some of my favorite parts were Ursula and Kiki’s exchanges over the creative process. For as much as it’s about a young girl coming of age, it’s also about struggles and rewards of good work, and not just for money – although the film certainly recognizes that necessity – but as something that we are compelled by, and how through doing the work we love, we form connections to one and other. Sometimes Miyazaki’s films have a tendency to overly romanticize labor as only a true workaholic like himself can. Here, he finds the right balance espousing between hard work and personal needs.

Something else that really moved me this time watching it were the simple acts of kindness and unwavering support Kiki finds in her new community. The bakers take her in and treat her like a daughter; Tombo presents her with an invitation to a party to spend time with him and his friends; the old women bake her cake to cheer her up when they know she’s depressed after losing her ability to fly. So much kindness, motivated only by a desire to see a young woman reach her full potential. It makes me want to cry just thinking about it.

But in case you haven’t watched it, please don’t think that this is some emotionally turbulent meditation on art. Above all Kiki’s Delivery Service is charming, romantic, funny, and beautifully animated.

There are lots of small flourishes in the animation that only become more impressive every time you watch it. There has never been a live action film that portrays flight in a way that simply feels right in the same way Ghibli films do. Whenever Kiki takes to the sky, I would think, yes, that’s exactly what it looks like when a witch flies on a broomstick, before realizing how ridiculous that sounds. To me, that’s the true power of animation: to make the unreal realer than real. Can you imagine how awful and fake this would look in live action1?

Yet as realistic as the animation can be, Miyazaki and his animators aren’t afraid to take advantage of the of the format. The way Jiji pretends to be a lost toy after Kiki’s first delivery hits a snag, standing perfectly still, even when thrown or carried in a dog’s mouth are hilarious, and make him feel exactly like an inanimate toy without ever changing his model. You really can’t describe it in words.

I don’t think it always occurs to people just how incredibly well thought out and executed this kind of animation is when you’re watching it. It’s easy to forget that every inch of every frame has been thought out ahead of time, where it is, when it moves, how it moves. It is in the way beads of sweat start to cover Jiji’s entire body as he draws closer, the way he shivers each time the next-door white cat rubs up against him, and the way the changes in direction midair are reflected in the way Kiki’s dress moves. It shifts from realism to cartoonism (is that a word? I’m making it a word) seamlessly in a way that always feels natural.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the scenic backgrounds. This time, I paid special attention to the architecture of the city. The signage around the city is in German, but the aesthetic of the buildings is a mix of various European influences. The forest where Ursula lives feels like it was ripped straight from a fairytale. There’s also something about the way the ocean is rendered that feels distinctly European, and I don’t even understand what I mean when I type that, but I know it’s true.

I watched it with the latest edit of the English dub, most of which was recorded back in 1998. I despised dubbing back when I was young and snobbish about anime. Now I’m old, still a snob, but better educated on how dubbing and translation works, and I was able to better appreciate the nuance of the performances that I was too inexperienced to recognize.

A young Kirsten Dunst’s performance as Kiki sounded too childish to me when I first heard it all those years ago, but now I think she plays it exactly right. Being a young inexperienced actress in voice acting, some of her readings are a bit stilted, but she does capture that emotional turmoil of a young woman who wants to be taken seriously as an adult even when she’s acting like a child.

Phil Hartman, one of my favorite comedians turned voice actors of all time, is unfortunately miscast as Jiji. Many of the additional ad libs Hartman added have been taken out, but that his chosen sarcastic tone is still present, and it always feels off key when paired with the animation. This was Hartman’s final role before his tragic death, so it really hurts me to say all of this. It’s still a joy to hear his voice, and I laughed a handful of times, but then again, Phil Hartman could read the Declaration of Independence and still probably get some laughs out of me.

The performance that really impressed this time was Janeane Garofalo as the artist Ursual. She endows her with a genuine sounding confidence and passion for her art . The scenes of bonding between her and Kiki were some of my favorites, and they capture a older and younger sister vibe that fits perfectly.

I have no complaints. This is about as close to perfect a a film can get. The closest I can think to something being even slightly off is the dirigible (zeppelin) rescue action set piece at the end, which feels a bit tacked on and obligatory, but it’s executed so masterfully that I didn’t care. My favorite scenes, however, were just watching Kiki, and the others do the most ordinary things, like grocery shopping or helping in the bakery.

When Kiki sees the sign made of oven baked bread the baker couple made for her and she lights up, I teared up a little. The countless moments of empathy and kindness really got to me this time in an unexpected way. This world would be a much better place if every person on earth was forced to watch Kiki’s Delivery Service every so often to remind them, you might even say inspire them, to be a good human being.

I regret to inform you all that it has since come to my attention that I no longer need to imagine it.